Listening to the Market to Avoid “Blocked Pathways” in Commercialization

Nguyễn Đặng Tuấn Minh

In recent years, the phrase “commercializing research outcomes” has moved from technical workshops into high-level policy discussions. In Vietnam, this conversation is no longer limited to engineering schools or a handful of application-oriented laboratories.

Is our science produced merely for publication, or to solve real problems for society and the economy? Image: Nature/Jan Kallwejt

This shift is not unique to Vietnam. Around the world, universities and research institutes are undergoing a similar transformation—from the traditional “research first, application later” mindset to a more candid and pragmatic market-driven research approach.

Importantly, this does not dismiss basic science. Researchers should not be asked to give up fundamental inquiry to “go sell products.” What is changing is our understanding of the role of scientists and universities. Knowledge today is expected not only to be published but also to find its way out of the laboratory—to become products, services, policies, or tangible improvements in daily life.

From “research for publication” to “research for use”

The tradition of most universities—both in Vietnam and in advanced economies—has been to prioritize academic reputation: journal papers, patents, and citations. This creates scientific prestige and a strong knowledge foundation for the country. Yet, it also has limits: many high-value research outcomes stay on paper or in project reports because they were never tied to real user needs.

Market-driven research begins with different questions: Who will use this? Would they pay for it—and why? Instead of waiting for companies to knock on the lab door, research teams proactively explore the market, interview users, talk to industry leaders, and validate needs. They do not wait for assignment—they move first.

This approach pushes scientists beyond the familiar role of “knowledge creators” to also become “value creators”—a far more challenging expectation than many people realize.

When the laboratory is no longer the final destination

In the U.S., programs like NSF I-Corps and SBIR have reshaped commercialization. Research teams must go into the field, talk to dozens of potential customers, and confront the blunt question rarely heard at academic conferences: “Do I really need this?” The goal is not to turn scientists into salespeople but to reveal that what they consider “important” may not match what the market prioritizes. This process can lead to product adjustments, changes in research direction, or even abandoning original ideas for more viable ones.

Globally, strong ecosystems embrace both academic research and market-driven pathways rather than forcing one to mimic the other.

Korea involves industry and investors early by asking: “Who will use this technology, and in which value chain?” Universities in Australia and the U.S.—such as the University of Melbourne and Ohio State—operate dual-path commercialization models: one traditional (IP licensing, spin-offs), and one flexible (early collaboration with industry even before a product is finalized).

Middle-income countries like Egypt, the Philippines, and Kenya are building TTOs, mentorship programs, and seed funds to help researchers move from the lab to prototypes and early market engagement. They view knowledge transfer as a public mission, not only a revenue opportunity.

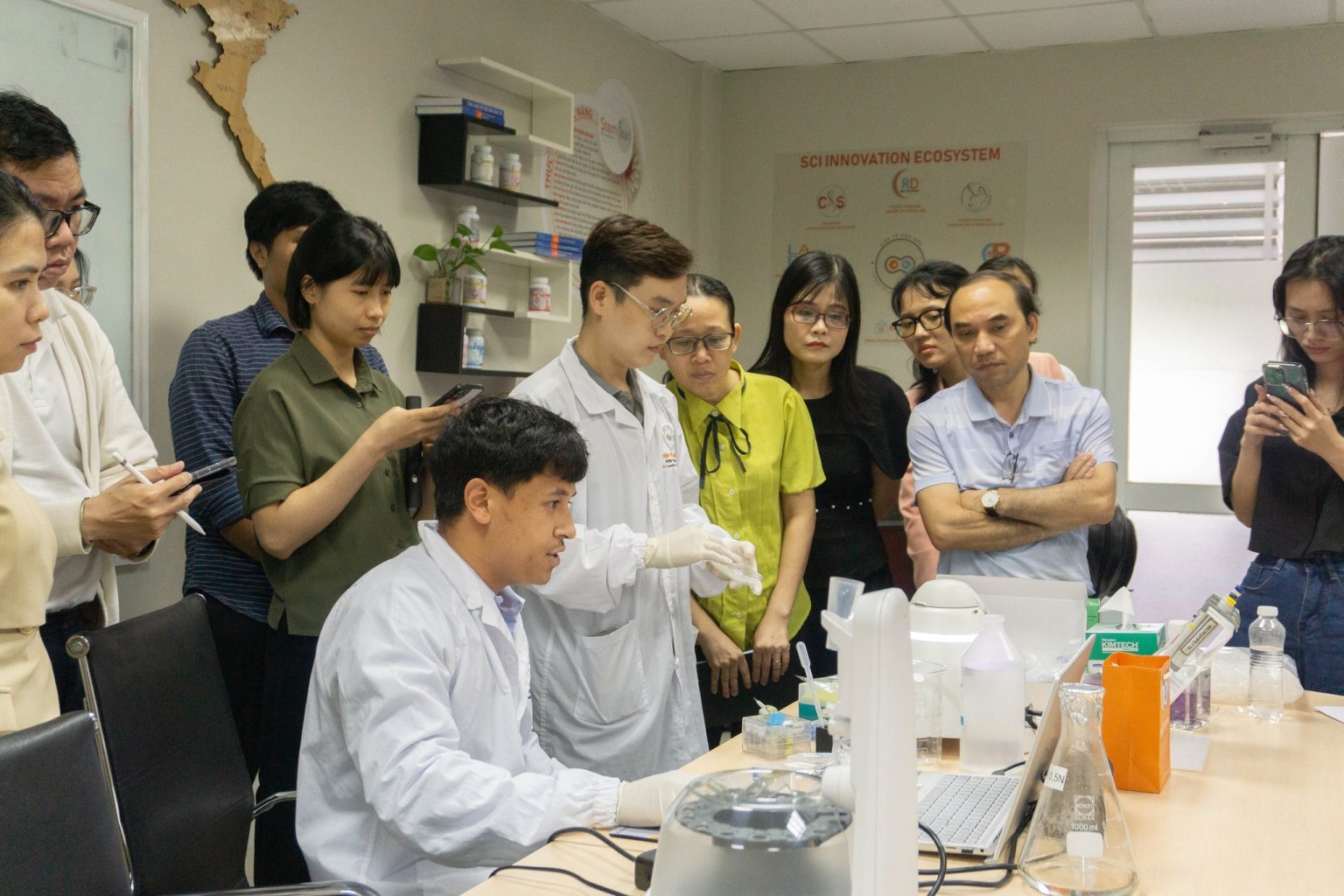

A workshop on exosome isolation techniques—ultra-small extracellular vesicles secreted by cells that contain DNA, RNA, and proteins and have numerous applications in medicine—organized by the Stem Cell Institute, University of Science, Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City, brought together hospitals and research institutions from across the country. Photo: Stem Cell Institute

Statistics show why this matters. Universities using market-driven approaches often generate three times more spin-offs, five times higher licensing revenue, and two to three times higher real-world adoption compared to publication-focused models. When the market is heard early, the path to market is far less congested.

A different logic of success

In traditional research, the process begins with the researcher’s idea, and success is measured by publications and patents. Businesses—if involved—appear at the end to license or adopt the technology.

Market-driven research begins with real user pain points: What is the real problem? Who faces it? Why hasn’t it been solved? Would they pay for a solution? Success is measured by tangible impact: revenue, spin-offs, high-quality jobs, or improvements in social challenges such as environment, public health, or food security.

The workflow also changes—from linear (Research → Application) to iterative (Research ↔ Validation ↔ Market Feedback ↔ Adjustment). Products do not emerge fully formed in silence; they evolve through continuous dialogue with real users. As a result, commercialization is faster, not because of shortcuts but because late-stage trial-and-error is reduced.

Vietnam: policy momentum is here—execution is the real test

Vietnam’s 2025–2030 period is shaped by a new policy mindset. The Law on Science, Technology and Innovation 2025 and Resolution 57 emphasize linking research with market capability. Decree 271/2025/ND-CP introduces benefit-sharing mechanisms, expands autonomy, and encourages collaborative technology transfer instead of handoff-style assignments.

From global experience and emerging domestic models, several practical, low-cost but high-impact steps can be taken:

1. Build market-research capacity inside universities.

Scientists trained in labs and publications cannot be expected to naturally converse with industry. Skills like understanding pain points, interpreting sector trends, and interviewing users must be taught—many countries integrate I-Corps-style training into graduate programs.

2. Make benefit-sharing clear and fair.

If scientists are expected to join commercialization, they must be compensated appropriately—not merely thanked in final reports. Transparent revenue sharing, IP licensing benefits, and equity stakes in spin-offs build trust and motivation.

3. Bring enterprises in at the beginning.

Treat businesses as co-designers of research problems. They know where bottlenecks are in production, logistics, standards, and global value chains.

4. Pilot an “I-Corps Vietnam” program.

Provide small grants not for more experiments but to meet the market, gather real feedback, and adjust assumptions. Only teams that validate real demand receive further funding.

5. Foster the idea of “scientist as potential founder.”

This does not mean forcing all faculty to start companies. Rather, it recognizes that labs can be the birthplace of science-based startups, and scientists can become co-founders or scientific advisors—with legal protection and university support.

Countries like the U.K. remind us that commercialization is slow work. University College London invested nearly a decade in spin-outs before seeing substantial returns—and remained patient because it was building foundations, not chasing metrics.

As one UCL technology-transfer director noted: “It took us 30 years to get here.”

Commercialization is not an overnight miracle—it is a shared learning journey between universities, businesses, and society.

If Vietnam wants science to become not only a source of pride but a competitive capability, the path lies not only in policy documents but in changing daily habits: taking scientists to the market, bringing businesses into the lab, and accepting that early “no-revenue periods” are normal in building long-term impact.

Knowledge truly lives only when it steps outside. The rest—patience, endurance, and mutual trust—is up to all of us.

(Published in Tia Sáng, Issue 21/2025)